The girl who carries water

Wide spreads of golden sand with impressions of the wind leaving wavered lines on its body. Red turban clad, white kurta - dhoti suited and leather chappal booted men. Sand dune shaped camel bodies walking along the expanse, tagging along. Parched throats, sweaty moushes, burning feet. And there she is, the glint of hope.

Appear and disappear.

The mirage of water. With unfaltering dedication they keep walking on their path through flat roofed houses on one side and matka appareled women bowing down to her on the other. Camels, chinkaras, crocodiles alike, all by her side.

And there she finally comes.

v

v

v

She tickles herself through rough and vain

Oh why oh why does she feel this way?

The need to disappear is a strain

yet she flows all through her pain

Guarded by her men on both sides,

She has no voice so be by her side

Be the ear she earns to find

Be her voice as she struggles to be kind

One day she will blow up and destroy,

Do we not see it come through

Come through to you?

Come through to me?

.

Why do we deny that her kind voice.

Click on the 'Matka' to view the broken present

{scroll up to re-explore}

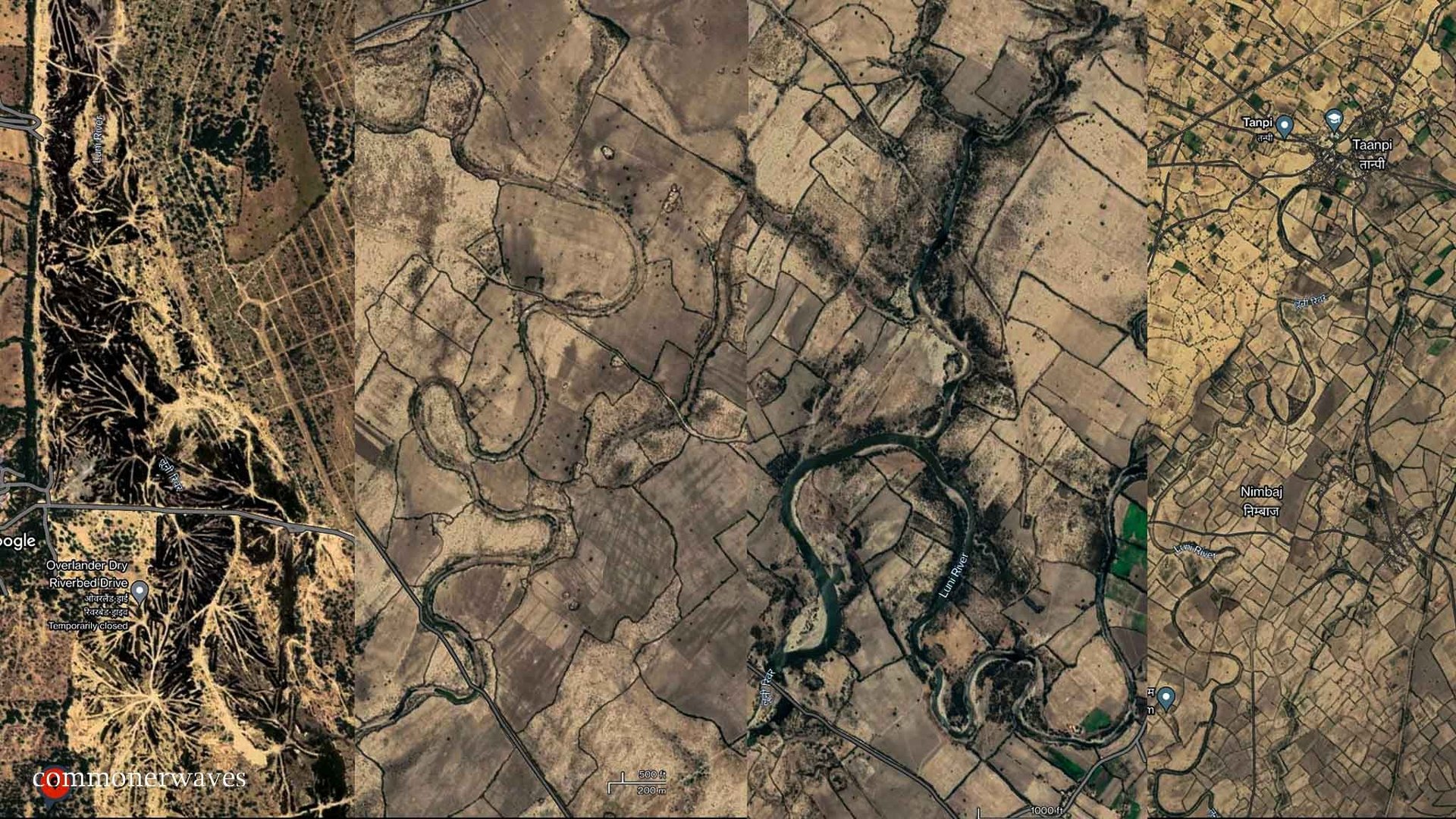

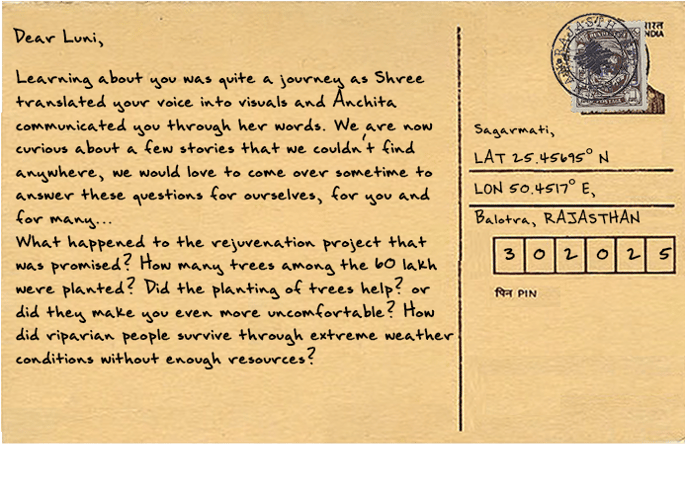

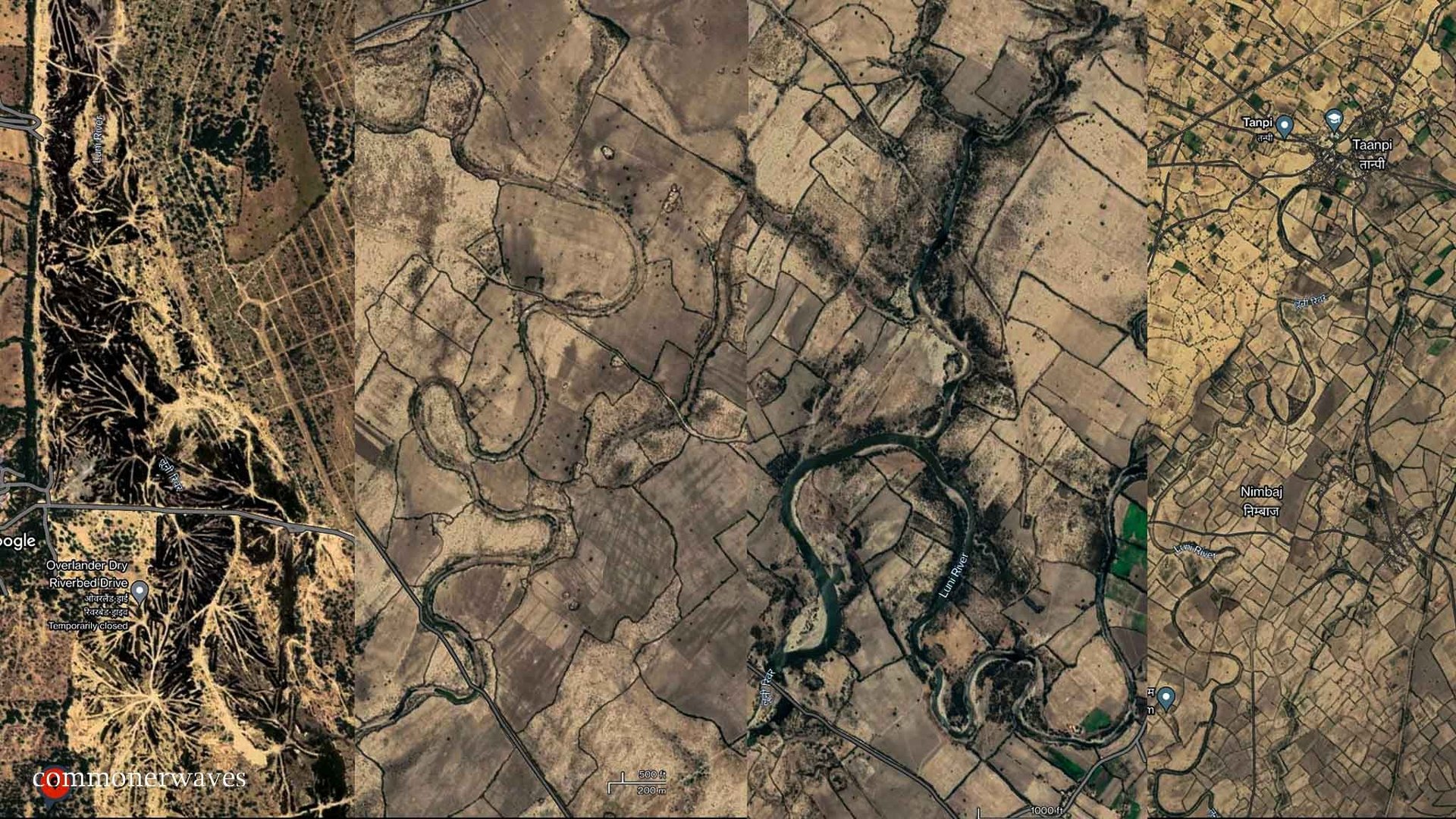

Through the vedic kingdom of Matsya, in Rajasthan, she tip toes slowly through the wide and dry expanse of the Thar. They call her Salila - The girl who carries water. She prides herself in being the largest flowing river through the arid regions of desert land surviving all along, mysteriously taking forms that confuse the tastebuds of her neighbors..

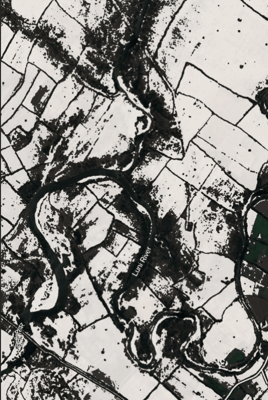

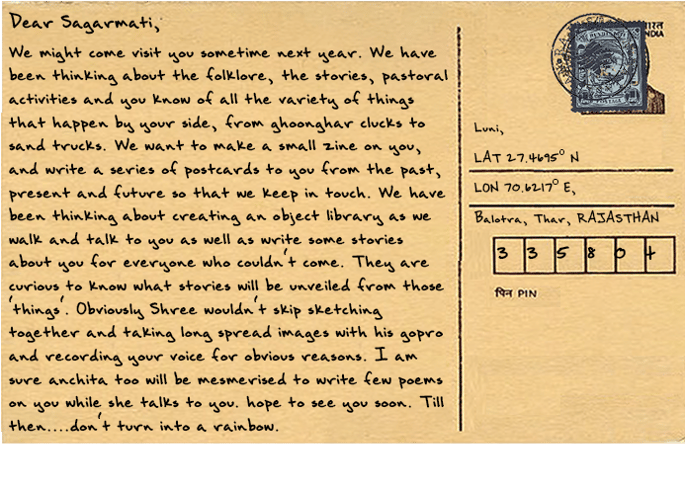

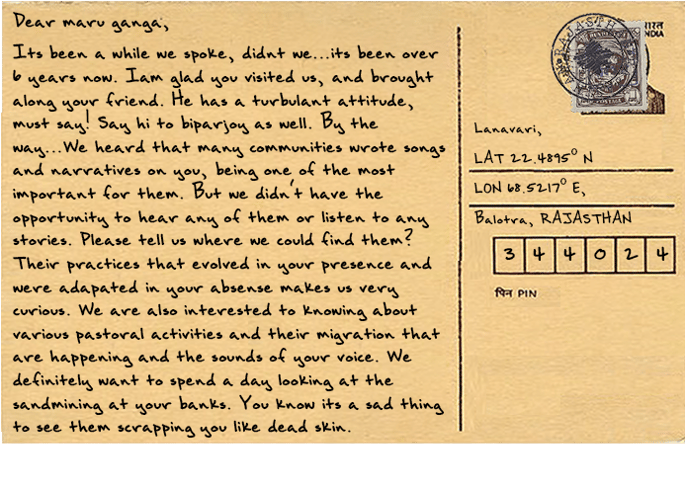

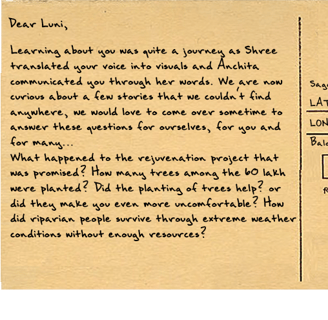

She takes birth in the Pushkar Valley of the Aravalli ranges. The first 100 kms of ground water in her catchments is sweet to the palettes and fresh, suited for all those that wait for her at the bank. But in the Jojri and Bandi catchment near Balotra, she transforms and is given her name in all celebrations, Salila to Lanavari or Luni. From the girl who carries water to the woman who carries salt, she flows downstream gathering her saline swell, scraping through the salt heavy limestone laden rocks and soil. Intolerant to the human tongue, but faultless for the migrating camels and 27 aquatic species she holds, she becomes known as a pastoral river feeding the thirsty and saline tolerant crops on the way.

She is wedded off to a land still unknown to us. As per Rajasthani tradition, a bride comes home to her “maika” during childbirth and returns to her “sasural” soon after. The Luni’s arrival, you can say, is somewhat similar. In the monsoons her belly protrudes, as her body is lined up with gushes of water flowing from below and above as she receives nearly 320 mm of annual rainfall majorly between July and September making her a seasonal river.

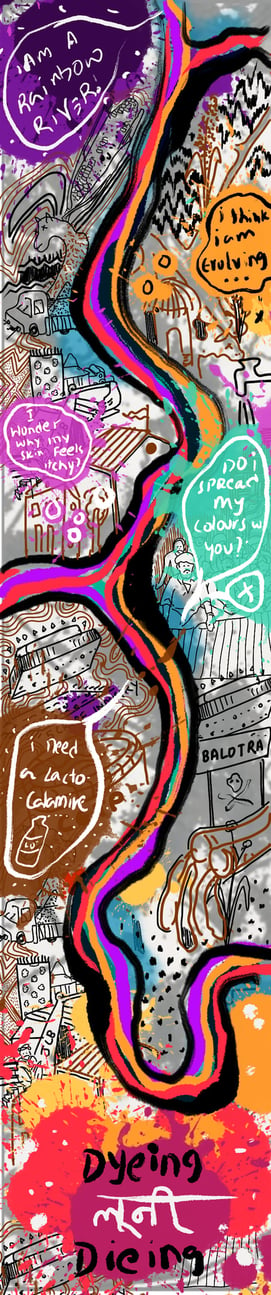

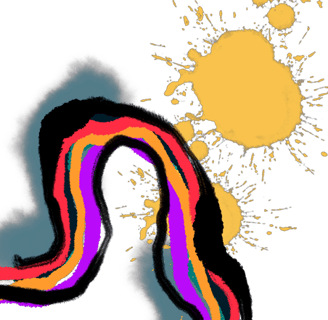

She feels overwhelmed now as she comes back, her flavours begin getting diluted. It is ironic to see how these rivers which kept us alive are killing us today due to their toxic and hazardous composition. Masses of textile factories, majorly in Balotra and Pali, feed her with their colour and stench. She mesmerizes us uncomfortably with her blues and greens, sometimes red patches with foam on her body. Beware it isn't snow in a sandy desert, it is poison from the mostly cotton textile industries which utilize artificial dyes and anionic detergents for manufacturing their products.

A shutdown of 800 of these factories was demanded in accordance to the green norms by the pollution board. Even Though the river did begin getting her life back, the economic lives of the workers who worked in these factories were at stake. Losing a job would mean losing the economic stability in addition to their already damaged crops along the bank. In 2018 the National Green Tribunal declared the Luni unfit for irrigation in addition to the already damaged ground water that affected the potability of water in wells. While the level of chloride suggested by WHO has 250 mg/L, the polluted Luni has a mean of 680 mg/L among other topsy turvy levels the river now provides its inhabitants with. The health of inhabitants in this region has been at stake with dysentery, cholera and lung diseases knocking at the doorstep.

Extensive bouts of drought and flooding have oscillated through the landscape so much that she is disoriented. When to come home to her maika and when to go back to the place she belongs to now is a matter of utter chaos leading to extremities that she provides her neighbors with. The river last flowed with natural rainwater in the 1990s. After that, because of successive droughts, it has never seen any water apart from the effluents discharged in it by the textile units of the town. The river went dry. As time passed she barely came back home anymore.

During a stint of heavy rains, the overswelling of the chemically polluted river let its waters into the crop fields of the Balotra division affecting the sustained production of wheat, gram, bajra and other seasonal crops in the basin. That’s the nature of a river. A body that feeds her neighbors and tributaries with utmost kindness but in turn equally shares her damages, her pain and happiness with all those around her.

Everyone was in a frenzy. Children raced along the river bed not too deep anymore and perfect for them stand in, crocodiles wore their bodies bear, exposed to the shallow water struggling to stay alive, the pollution control board locked in their offices figuring out what the next policy to their mismanagement should be, farmers along their their wilting crops looking at the sky, eyes closed, palms joined and tears evaporating before they dropped from their chin. Their wrinkles on their foreheads as dry as the soil. The saline water from their tears reminds them of their Lanavari. But what could they do? Who would they ask where the river has gone and why ?

And she? She was being the biggest rebel she could, not giving in to the disappointment her home gave her.

But to coax her to come back, nine major irrigation projects were set up through forest department initiatives. The government planned on planting about 60 lakh trees along the banks of the rusted river heading to the type of landscapes she encounters on the way. The aim of the project is to develop dry land forests on both sides of the river, control soil erosion as well as increase the ground water recharge levels to regenerate ecosystems and improve the livelihoods of people in the region. While the initiative seems thoughtful only time will tell how well it serves its people and her. Maharaja Jawai singh built a dam on her tributary the Jawai to cater to the people of his land in the early years of 1957 when the Luni had been flowing in all high spirits. The release of water from the dam, built on Luni river’s tributary Jawai, has been a matter of dispute since its construction in 1957.In the last several years, farmers from Jalore have been demanding that one-third of the water stored in the dam be released into the Jawai river as a natural flow, which will increase the ground water level in the region and help in the irrigation of crops.

She is of the earth. yet who owns her she is painstakingly blinded to.This explains why the people of arid zones live on the margins of scarcity. Mismanagement, deviation from the voices and ways of the land itself. While the many inhabitants as a traditional practice are nomadic and keep following the river in search of food and water, their movement now is restricted too. Having to change their migratory routes in search of fodder for cattle, disrupting ecologies of other animal habitats that were dependent on this migration. Yet despite all these struggles, conflicts over scarce resources never come to an end.

Owing to the topography of the river, the lands are known to be abundant with one resource that floods its away through thick and thin along the waterless coast. Sand. One by one all parts of her are ripped away. The world economic forum reports that Sand is the second-most exploited natural resource in the world after water (7). And so the government has had its eyes on the micategorised “wastelands” of the Thar ever since sand was unavailable in other regions. Rajasthan had, in 2015-16 used 100 million tonne of river sand

Rajasthan has 14 million cattle as of 2019, and the highest population of goats (20.8 million), 7 million sheep and 2 million camels. The mining projects along the banks will in time change the course of the river taking away the water that is used for agriculture as well as change the migration routes of pastoralists who heavily depend on the river for water. The basin home to Indian Bustard, Black buck and Chinkara begin shying away from the nakedness of the bed. When the mining companies come in, they strip the land of all the succulents like the Dhok tree, shrubs and trees like the kera and dhoop that blanket the sandy terrain. The Luni helplessly watches her counterparts wrenched through the land as her body gets ripped apart and tractors dig through her without consent. In this regard, Indigenous threatened species such as the Gangerun shrub plant of cultural value medicinal and fodder value seize to exist. The ecological cycles are disrupted in the process. She loses the chirps of birds, whispers of the insects that used the terrain as breeding grounds and kept her company while she swayed through the land. They are forced to leave as the temperature of the area begins to rise. The heat waves in the already boiling realms of the Thar.

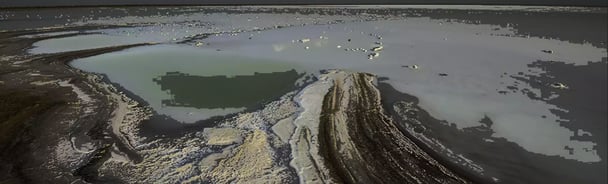

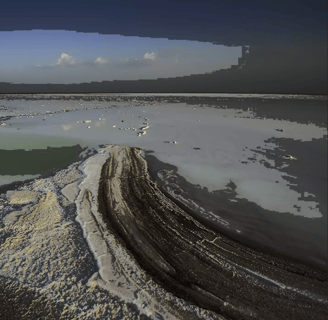

Her final destination is inconspicuous as she fades into Rann of Kutch being the only river to do so, her coming and going through the years of exile. She comes and goes, rebelling the acts on her, fighting for herself. In defense, in revolt as a testament to the power she has, having survived the eeriness of the hot, sand laden, unfairly damaged landscapes of the western most parts of the country. She leaves her brown desert and enters her white land to probably protect herself from any further atrocities she might have to face? We see her disappear again at the onset of winter where water will once again evaporate leaving the river bed naked, this time, unapologetically.

She is vulnerable. Her anger is taken over by desolation as she watches in despair as she trickles and disappears.

A crazy battle in the skies needed to be presented to her to bring her back. To cheer her up. After 6 whole years of her exile, the destructive to other cities, yet joyously productive rains for the Thar, the cyclone Biporjoy welcomed Luni back as she paraded royally through her tracks that were now almost laden with bare stones, the river bed pulled out and a landscape she did not recognise as much. Prayers and flowers were devoured on her. She had come back to reclaim the land that was hers and cleanse the atrocities she faced, cleaning all the toxins out of her body with the heavy flow she brought in at Balotra.

She is vulnerable. Her anger is taken over by desolation as she watches in despair as she trickles and disappears.