"Unlike the sudden death that is experienced at the shot of a bullet, landscapes experience a slow torturous death as its breath is slowly taken away from it."

Know about us

v

v

COVER LETTER

Today environmental conservation protests, climate futures forums and other organisations have begun springing up, but what does environmentalism and “save the environment” mean to the ones facing the brunt of the slow violence in their neighborhood? How does one live at the margins of scarcity and yet adapt through its repercussions? This state of destruction takes place slowly where a misguided policy or design or warning made and implemented unfortunately sees its results only over the course of many months, years or generations. The damages of which are often too late to revert to the ecologies that once were.

Yet the people of the land survive. They see, They learn, jugaad their ways of living and come up with undocumented ways of survival. They live through songs, stories, myths and legends as a form to remember the landscapes that are being taken away.

Our interest in this fellowship would be to document these stories of adaptation and survival. What are the ways in which pastoralists, farmers, locals of the land adapt and survive through all the atrocities of human - development conflicts that come their way? How have they historically survived through the generations of disasters of droughts, floods, rising temperatures of days and bone freezing nights to the current scenarios of sand mining, dam constructions and factories. What are the ground realities and opinions of commoners for the environmental policies that have been put in place for them and the river?

Endangered living museums of Luni

What are their stories of resilience they bring to the table?

Aritakula Shree Tej

Anchita Kaul

As a product designer, I have spent the past year crafting toys and games for children. Through this journey, I have come to recognize the growing disconnection of today's children and young adults from the natural world. In a world where landscapes are rapidly disappearing and human ego is soaring, I believe that it is essential to instill humility in both children and ourselves. Through the mediums of storytelling in the form of games, theater and non fiction stories I look to rekindle a connection to the fundamental roots that sustain us and foster awareness. My experience as a learning designer also fuels my interest in the artifacts used to educate and adapt to diverse contexts, driven by a curiosity to unravel how we and our natural environments have been learning, evolving and adapting across generations.

You can call me a design traveler having embarked on a unique journey after leaving a multidisciplinary designer job that involved crafting diverse products, systems, research tools, and websites along with the world of customizable electric bicycles and biomimicry. Since then, I have been traveling through India, immersing myself in local experiences, gathering stories, and uncovering the ingenious concept of "jugaad." Creating object libraries has become a pivotal method for me to understand different locales and generating valuable research. Staying with commoners, savoring local cuisine, and engaging in random activities, I try seizing the opportunity to learn from the smallest of things.

A brief introduction

Theatre

Illustration

Wall Murals

Bicycling

Product design

Music

Game design

Trekking

Publication design

Creative writing

Research

Learning artefacts

Travelling

Storytelling

Grassroot projects

Documentation

Naturewalks

Oral history

Libraries

Archives

Journaling

Food libraries

Anchita

Material exploration

Objects

Archeology

Textiles

Shree

Handi craft

Residing in the bustling urban centers of Mumbai and Hyderabad, we've witnessed the unfortunate transformation of the Mithi and Musi rivers into virtual pools of garbage right before our very eyes. It is another classic example of the ongoing conflict between human development and the environment. This constant cycle of destruction made us ponder about who gets to decide what should be done with these common resources? All too often, the responsibility for instigating change and environmental preservation is placed squarely on the shoulders of social workers, activists, and conservationists, overlooking the shared responsibility that commoners, like us, bear in preserving our environment. It made us realise how disconnected we are from the very land we live on and poses a big hurdle in nurturing empathy for these sources we so easily contaminate and exploit.

Throughout history, communities and humankind have relied on storytelling as a means to bridge the gap between the tangible and the abstract to build connection. Whether through folklore, songs, or cave paintings, these stories have forged a language of connection to the intangible aspects of life, earning respect because they serve us. Our creative practice has thus been largely motivated by this to make the seemingly unrelatable, relatable, and to foster a connection to the land for everyone who calls it home.

This led us to the semi-arid villages of Bidar, North Karnataka, for our final year thesis. Anchita delved into researching and documenting narratives surrounding the self-sufficiency of farmers in the region using food as a medium for storytelling owing to how food is reflective of multiple layers of one’s life their social status, cultural sensibilities, environmental impacts, policy decisions, and how these factors influenced their way of life. This culminated in a theatrical play and a food library that bound together the stories we collected, serving as a tool for further research.

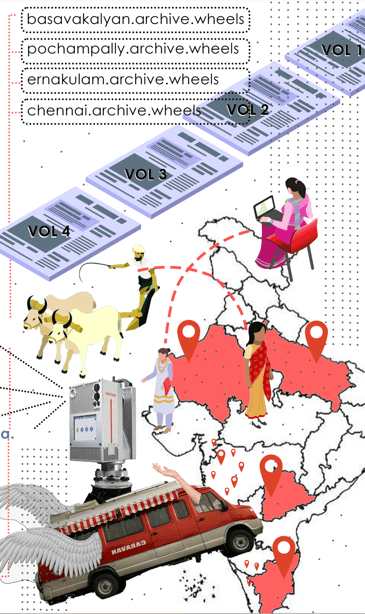

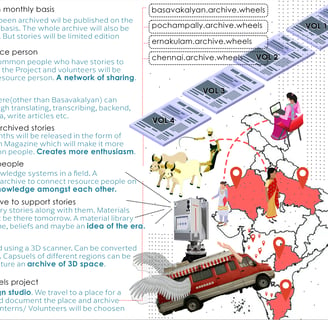

Shree, on the other hand, embarked on a mission to create a living archive of local stories centered around water systems in Basavakalyan. Along the way, he discovered a gap in the documentation of commoners' perspectives and their agency in telling their own stories. These stories started to revolve around caste, religion divisions, regional politics, and the emergence of new ideologies. The project finally incorporated creating project booklets, forming volunteering teams, and conducting archiving drives in collaboration with Dodda-Appa-Appa B.Ed college students through participatory design methodologies.

This, combined with our fieldwork experiences in Kutch and Assam documenting craft clusters, and in Kashmir documenting soundscapes, myths and legends of the rivers, among other experiences exposed us to various multifaceted aspects of our social systems. We realized that while these layers of our land, cultures and power structures are interdependent, the perspectives of commoners are often overlooked. When we do encounter their stories on the internet, they are often sensationalized or reduced to flashy news through broadcasting channels depriving us of the true essence of grassroots knowledge. In addition to this we have seen through our work that while deeply researched field narratives are typically analyzed and published as scientific research and data, these forms can be incomprehensible to the common person. This has helped us curate a practice through mediums that are accessible and understood by the general public that helps them build a closer relationship with the stories they read and interact with.

Our interdisciplinary education in design at Srishti Institute of Art, Design, and Technology equipped us with the skills to explore various forms of creative expression that encompasses visual documentation, poetry, fiction inspired by real stories, theatre and soundscapes, and object material libraries. It encouraged us to approach each context with an unbiased lens, allowing us to document narratives without preconceived notions while adapting our medium of storytelling to the specific context we were working in. This also helped us become curious through a systems-centric lens, enabling us to breakdown the complexities of various issues.

Why do we want to do this fellowship ?

This persistent need to convey the cultural realities and folklore for the conservation of natural landscapes and traditional practices has always driven our creative practice. We believe that this desire to bridge the gap, empathize more, and redistribute agency, all while sparking conversations about the paradoxes that persist in our times, is in alignment with the vision of the Moving Upstream fellowship.

The larger questions we keep coming back to are asking - Who makes decisions for the land inhabited? Whose stories get documented to be passed on through generations and cultures? Who makes history (his-story)? Who and what has the value to be exhibited in a museum? Driven by this, our mission in the coming future is to eventually build a ‘studio on wheels’, A living mobile studio that documents local stories and knowledge systems based on participatory design approaches. The vision is to document vernacular cognizance and build hyperlocal ground level solutions in collaboration with people across generations. The hope is to generate a reflective system of understanding how across the levels of decision making, power structures get translated on ground. We have seen first hand how locals at the grassroots know their land, they know how to listen and act as per the calling of the land and their communities. Thus, the idea is to build a larger inter-cultural community at the intersection of social and creative practice where people closest to the land have the agency to tell their own stories and document the revival and survival of landscapes as per the ancient knowledge systems they have been guided by.

While we have already started building on this journey of ours with documenting stories at a small scale as we travel around India, the Moving upstream fellowship comes to us at just the right point in our journey with a similar vision.The mentorship, with experts in the field and a community of fellow explorers is extremely valuable to us to help with our growth in further breaking down and building our practice. The fellowship will help us learn through the experience of mentors and the nuanced feedback they have to offer through their own similar experiences in the field. It will help guide us through our own journey for the future vision we have.

Walking as a medium

Our human audio-visuals have failed to keep pace with the rapid movement that unfolds around us. When we slow down, it feels as though the landscapes begin to communicate with us through their movements. We witness their interactions, not only with each other but with us, too. They possess the unique ability to convey messages to us through an evolved, silent, and language-less manner.

Our walking exploration has led us to villages in North Karnataka and Kashmir which granted us a profound understanding of the significance of a slower pace in our fieldwork. It instills a sense of calm control over time, allowing us to immerse ourselves fully in the process rather than rushing towards the destination. This approach is neither overwhelming nor intimidating for the people we engage with, as it serves as a simple means of traversing from one point to another helping us shed our pride, ego, and backgrounds, placing us all on equal footing. It allows for versatility, permitting everyone to interpret the surroundings in their own unique ways to build perspectives, awareness and most importantly narratives.

It encourages us to slow down and truly "observe" with all our consciousness, as opposed to merely "seeing" for a fleeting moment. We learn to "listen" rather than just "hear" and "feel" rather than merely touch. This, in turn, opens up opportunities for us to translate our observations and conversations into various forms of expression.

(part of Kashmir Project)